143. Solitude and Education, Part 5: Thoreau on Nature and Virtue

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), in his book Daybreak (1881), wrote:

“On Education. – I have gradually seen the light as to the most universal deficiency in our kind of cultivation and education: no one learns, no one strives after, no one teaches – the endurance of solitude.” (aphorism #443, translated by Hollingdale)

But why the endurance of solitude or, to use Philip Koch’s definition from his book Solitude: A Philosophical Encounter (Open Court, 1994), this “time in which experience is disengaged from other people” (27)? So far we have considered four closely related answers: (1) solitude can help us find our authentic individuality; (2) solitude can help us understand other people and things more objectively; (3) we should embrace solitude if we are to truly read in order to encounter greatness and expand our self; and (4) solitude can facilitate a state of disinterested contemplation which can help us overcome our cravings (go here for these posts). Now let’s consider a fifth answer that will expand our cumulative case in defense of Nietzsche’s claim:

(5) We should endure solitude in order to feel a primal sympathy with nature – a sympathy which can facilitate the development of many virtues.

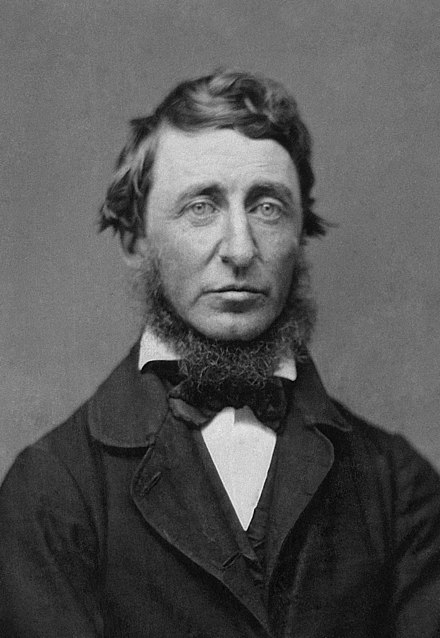

Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854) will help us understand this romantic proposition. Philip Cafaro, in his book Thoreau’s Ethics: Walden and the Pursuit of Virtue (Georgia: 2004), shows how Thoreau’s views on solitude help facilitate the development of six genuine virtues: freedom, self-reliance, personal reflectiveness, personal focus, and connection to nature (117). In previous posts I have emphasized all of these virtues except the last. So in this post I want to explore the connections Thoreau establishes between solitude and nature. We will see that these connections can indeed facilitate the development of the above virtues and one other besides: love.

Henry David Thoreau

In his chapter “Solitude” he notes “I have never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.” And he certainly finds this companion living out on Walden Pond. What is remarkable is how this solitude reveals his intimate connection with nature:

“This is a delicious evening, when the whole body is one sense, and imbibes delight through every pore. I go and come with a strange liberty in Nature, a part of herself. As I walk along the stony shore of the pond in my shirt-sleeves, though it is cool as well as cloudy and windy, and I see nothing special to attract me, all the elements are unusually congenial to me. The bullfrogs trump to usher in the night, and the note of the whip-poor-will is borne on the rippling wind from over the water. Sympathy with the fluttering alder and poplar leaves almost takes away my breath; yet, like the lake, my serenity is rippled but not ruffled. These small waves raised by the evening wind are as remote from storm as the smooth reflecting surface. Though it is now dark, the wind still blows and roars in the wood, the waves still dash, and some creatures lull the rest with their notes. The repose is never complete. The wildest animals do not repose, but seek their prey now; the fox, and skunk, and rabbit, now roam the fields and woods without fear. They are Nature’s watchmen – links which connect the days of animated life.”

In solitude we have an opportunity to sympathize with nature and to realize that nature sympathizes with us:

“The indescribable innocence and beneficence of Nature—of sun and wind and rain, of summer and winter—such health, such cheer, they afford forever! and such sympathy have they ever with our race, that all Nature would be affected, and the sun’s brightness fade, and the winds would sigh humanely, and the clouds rain tears, and the woods shed their leaves and put on mourning in midsummer, if any man should ever for a just cause grieve. Shall I not have intelligence with the earth? Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself?”

In these passages Thoreau appears to be experiencing something William Wordsworth, in his poem “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood”, beautifully described as the “primal sympathy” which enables us to resonate with everything. But this mutual sympathy appears to flow from more than our shared physical substance. In “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey” (1798) Wordsworth writes:

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

David Casper Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818)

Perhaps it is this dynamic spirit that forges what Thoreau refers to as an “encouraging society” which “may be found in any natural object, even for the poor misanthrope and most melancholy man.” Natural objects, when encountered in solitude, can offer a form of social fellowship to those for whom human society is so problematic. They can also assuage one who feels, like Thoreau felt for one hour, “oppressed by solitude”. He explains:

“In the midst of a gentle rain while these thoughts [of oppression] prevailed, I was suddenly sensible of such sweet and beneficent society in Nature, in the very pattering of the drops, and in every sound and sight around my house, an infinite and unaccountable friendliness all at once like an atmosphere sustaining me, as made the fancied advantages of human neighborhood insignificant, and I have never thought of them since. Every little pine needle expanded and swelled with sympathy and befriended me. I was so distinctly made aware of the presence of something kindred to me, even in scenes which we are accustomed to call wild and dreary, and also that the nearest of blood to me and humanest was not a person nor a villager, that I thought no place could ever be strange to me again.”

The crucial thing to see here is that this sympathy, far from being something that remains an inner feeling, can have tremendous consequences for human society by showing “the fancied advantages of human neighborhood insignificant.” Rick Anthony Furtak explains:

“Considering the human being as “an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature,” rather than a cultural artifact merely (“Walking”), he looks to the nonhuman natural world and to our inherent “wildness” as a source of evaluation which can empower us to discover that the standards of our civilization are profoundly flawed….Withdrawing into the natural world allows us to view the state in a broader context and to conceive of ways in which social values and political structures could be improved radically.” (see the Thoreau entry in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

The experience of a natural sustaining sympathy can be the ground for social critique by revealing, through an often depressing contrast, the limits of, perhaps even the “insignificance” of, artificially constructed forms of sustenance. This revelation can then help us question our dependency on the so-called necessities of modern life. We come to see that many of the institutions, beliefs, habits, and cultural practices, far from sustaining us, are actually alienating us. Here are some examples from chapter 1 (Economy) of Walden:

- “We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate…. As if the main object were to talk fast and not to talk sensibly.”

- “This spending of the best part of one’s life earning money in order to enjoy a questionable liberty during the least valuable part of it reminds me of the Englishman who went to India to make a fortune first, in order that he might return to England and live the life of a poet.”

- “Actually, the laboring man has not leisure for a true integrity day by day; he cannot afford to sustain the manliest relations to men; his labor would be depreciated in the market. He has no time to be anything but a machine. How can he remember well his ignorance — which his growth requires — who has so often to use his knowledge? We should feed and clothe him gratuitously sometimes, and recruit him with our cordials, before we judge of him. The finest qualities of our nature, like the bloom on fruits, can be preserved only by the most delicate handling.”

- “Nations are possessed with an insane ambition to perpetuate the memory of themselves by the amount of hammered stone they leave. What if equal pains were taken to smooth and polish their manners? One piece of good sense would be more memorable than a monument as high as the moon.”

- “Most of the luxuries and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind”.

These revelations can, in turn, help us develop the courage to shed many of the unnecessary complexities of life. As Thoreau famously said, “Simplify, simply.” And this process of simplification can help develop the virtues of freedom and self-reliance. And when we have freedom from others and increased self-reliance we have the time and space to cultivate the virtues of personal reflectiveness and focus that help us become unique individuals.

But the sympathetic resonance with the “sweet and beneficent society” of nature also offers us the opportunity to develop the virtue of love if we can say, with Thoreau, “no place could ever be strange to me again.” This insight, one of Thoreau’s most powerful, has the potential to break down some of the artificial walls between us and offer us a glimpse of universal fellowship. A deeply moving passage from the chapter Spring provides an example:

Walden Pond

“While such a sun holds out to burn, the vilest sinner may return. Through our own recovered innocence we discern the innocence of our neighbors. You may have known your neighbor yesterday for a thief, a drunkard, or a sensualist, and merely pitied or despised him, and despaired of the world; but the sun shines bright and warm this first spring morning, recreating the world, and you meet him at some serene work, and see how his exhausted and debauched veins expand with still joy and bless the new day, feel the spring influence with the innocence of infancy, and all his faults are forgotten.”

The spring ice between us can melt away as it did on Walden pond revealing “innocent fair shoots.” So perhaps it is this belief in, and recovery of, innocence in ourselves and others through nature that allows us to overcome even the most extreme forms of human alienation. Thus nature can help us love our neighbors by enhancing their freedom to grow and transcend whatever is keeping them in bondage.

When we take all these ideas together, we see that a return to nature in solitude can help us develop virtues by allowing us to see our relationship to social practices and each other in ways that can make us more free, self-reliant, reflective, focused, and loving. With these virtues in hand, we can then return to society and hope to improve it.

To be sure, some of these romantic sentiments can be hard to embrace given the knowledge we have acquired from modern science. I mean, can we really sympathize with nature and believe that nature sympathizes with us? Isn’t this to engage in silly personifications? Can we really accept that nature, with all its violence and apparent indifference to suffering, is a generous society waiting to befriend even the most melancholy misanthrope? Can springtime really help us see vicious people as born anew? Can sympathetic feelings really be the ground for true social reform? Wouldn’t this ground need to include reason, law, and force as well? But to address these questions with reason and science seems inappropriate. If there is any truth to this romantic view it should be something directly experienced without, as Thoreau put it, “having many communicable or scholar-like thoughts.” Thus perhaps a return to nature in solitude is in order to see – ultimately to feel – if we can agree with these lines from Wordsworth’s poem “The Tables Turned” (1798):

One impulse from a vernal wood

May teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

For the final post in this series on solitude and education, go here.